The second round of the French presidential election is due on 24 April, and the imperilled identity of the country is the one indisputable thing that a majority of French seem to agree on.

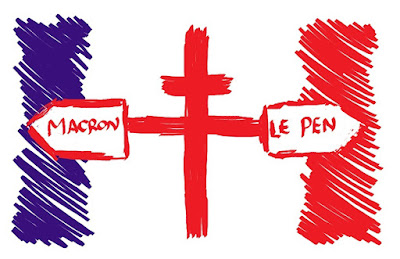

Both rival candidates, Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, are controversial, especially when it comes to their relations with French Muslims. Who is perhaps worse is not entirely clear.

Two demagogues?

Marine Le Pen compared Muslims praying in the streets, with the German occupation of the country. Emmanuel Macron stigmatises Muslims and cracks down on those who raise their voices in opposition to this. In addition, who can forget his steadfast defence of offensive drawings of the Islamic Prophet Mohammed?

Worst of all for French Muslims could be Macron's goal to rewrite Islam to be more liberal and appropriate to his vision of France. He also made an effort to close the French Council of the Muslim Faith, dissatisfied with it and with any perceived foreign influence, including simply the international communion that exists between believers across the world.

Unfortunately, France should simply be considered hostile to Islam. Between the two presidential candidates, Macron might be the more insidious, trying to actively distort Islam and interfere in the freedom of conscience.

Le Pen, despite probably having a more negative reputation with Muslims (similar to Trump), is just old-fashioned rather than insidious. She would not likely try to interfere in and pervert other people's faith, even if her policies would be more directly confrontational with France’s Muslim community, with such absurd measures as fines for wearing headscarves. It is also noticeable that Macron is a zealous Israel-supporter, going as far as to label Israel critics as enemies of the Republic, a bizarre attack that strikes directly at the consciences of Muslims more than Le Pen has done.

Civilisation anxiety justified?

Regardless of the outcome of the presidential election, France will struggle to reconcile the consequences of its imperialism and its attempts to maintain a culturally uniform nation-state. This could eventually result in separatism and violence in decades to come.

France’s differences from Britain are that Britain is not a secular state, and Britain accepted its overseas people as distinct cultures, with little interest in assimilation, as there is no Britishness to assimilate into (all aspects of our identity, from food to flags and even the Union itself, are the cumulative imperial booty acquired by Norman conquerors, so there is no core Britishness to be anxious about, like the core Frenchness).